Mastermind Masterclass

New Gene Information Page

Thursday, November 16, 2023

With the move from panels to whole exome and whole genome sequencing (WES and WGS) comes incredible opportunities for precision medicine, but along with that opportunity comes a host of novel variants that make it a challenge to scale variant interpretation workflows. Genomic scientists need detailed gene-disease relationships, gene information, and data on other variants within the gene to quickly analyze these novel variants.

Mastermind’s new Gene Information Page puts comprehensive gene information and ACMG gene-wide parameters for variant interpretation at your fingertips. This builds on Mastermind’s comprehensive view of all published variants within a gene, so you can find the answers you need from just one platform. With the Mastermind 3.0 release, the Genomenon team is the first to curate the clinical exome at the gene level based on ClinGen guidelines, considered the highest industry standard. Now, you can see a holistic view of gene information for rapid decision-making, especially for exomes/genomes and large panels.

In this Masterclass, Clinical product manager Dan O’Hara, project manager Betty Mathias, and Mastermind expert Denice Belandres will walk you through the new Gene Information Page and answer your questions.

You will learn how to:

- Streamline workflows by rapidly triaging variants to focus on known disease-causing genes

- Quickly uncover and interpret novel variants with useful gene and variant summary information

- Identify more disease-causing variants by reviewing all prioritized relevant articles with variant- and gene-matches

Featured Mastermind Experts

Dan O’Hara, PharmD

Product Manager, Mastermind

Denice Belandres

Field Application Scientist

Betty Mathias, M.S.

Project Manager

WEBINAR TRANSCRIPT

CANDACE: Hello, everyone, and welcome to the Mastermind Masterclass, where we will dive into our brand new gene information page. My name is Candace Chapman, and I will be your host! You’re probably here because you already have a Mastermind account, so you know that Mastermind is the most comprehensive source of genomic evidence, and can be used to quickly identify and review papers for patient diagnosis and treatment decisions.

You may have noticed that Mastermind is now the Genomic Intelligence Platform. That’s because it’s now much more than a genomic search engine. Mastermind provides a growing number of pre-curated variants, information on clinical trials and treatments, an associations page where you can see connections between diseases, genes, variants, phenotypes, therapies, and CNVs, and today, the gene information page. In today’s Masterclass, our Mastermind experts will guide you through the new page, which greatly expands Mastermind’s utility by providing comprehensive gene information, including gene-disease relationships, ACMG gene-wide parameters for variant interpretation, and other useful tools.

We’re really excited to share this presentation with you, but first, here are a few quick housekeeping notes. Some of the features our speakers will cover are only available in the Professional Edition. If, by some chance, you don’t have a Mastermind account, you can create one today by using the bit.ly link you see on the screen. It will also be dropped in the chat window. That will start you on a free trial of Mastermind Pro. As questions come to you, please drop them in the Q&A box to the right of your screen. If we run out of time before we get to your question, we’ll follow up with you after the event. Today’s webinar is being recorded, and a link will be emailed to you to review or share after we wrap.

I also wanted to share a link to our founder Mark Kiel’s ASHG colab presentation, which explains more about the scientific challenges of understanding gene-disease relationships and how we’re meeting those challenges with the gene information page. To watch the presentation, go to genomenon.com/ashg-2023.

Now, I have the privilege of introducing our speakers. First, Dan O’Hara, product manager for Mastermind. Hey, Dan! Dan was the driving force behind Mastermind 3.0 and all of what we’re covering today. He worked closely with our product, science, and development teams to make the gene information page possible, and we quite literally could not have done it without him.

Next, Denice Belandres, Genomenon’s field application scientist and Mastermind expert. Hey, Denice!

DENICE: Hey, Candace!

CANDACE: Denice provides technical support and training to Mastermind users at all levels, with a background in germline variant analysis and pre-implantation genetics in clinical NGS labs. She turns feedback into function, enabling the implementation of Mastermind for a variety of clinical use cases.

Then, we have Betty Matthias, project manager and variant scientist. Hi, Betty!

BETTY: Hello!

CANDACE: Betty earned her Master’s in human genetics and genomic data analytics, which focused on clinical genetics, variant curation, and bioinformatics at Genomenon. In addition to managing members of the variant curation team, Betty focuses on internal procedures and strategy. All right, well, Dan’s going to get us started. Dan, take it away!

DAN: Thank you, Candace. Hi everyone, my name is Dan O’Hara, and I’m thrilled to have the opportunity to talk about Mastermind 3.0 today. Before I do that, I’ll give some brief background about myself and what I do. To start off, I have a deep passion for helping patients. That comes from my background as a pharmacist, and I developed a love for genetics and technology from my time on the translational oncology team at Foundation Medicine. Thankfully, I found myself joining Genomenon 18 months ago, where I now get to combine technology and genetics to help professionals like you all treat, diagnose, and ultimately improve patient lives.

I’m the product manager here at this incredible company, and I get the opportunity to work directly with passionate people to build the best Mastermind possible for clinicians and researchers. I work extremely closely with our customers to understand how we can build Mastermind in a way that complements their daily workflow, and I pair that with an immense amount of market research and UX/UI design to plan and develop our roadmap. So remember, always reach out to us with your feedback and suggestions, because we are listening to you, and we are delivering.

I understand we have a mixed audience today, so for those unfamiliar with our software, I wanted to introduce you to Mastermind briefly. Mastermind is a clinical decision support tool with thoroughly indexed genetic information from scientific and medical literature. We have over 5,500 curated genes, 9,000 gene-disease relationships, over 9 million full-text genomic articles, 3 million supplemental data sets, 23.5 million variants, and more passion than we can possibly quantify. All this is achieved by Genomics Language Processing, or GLP, which is a patented process that indexes genomic data to ensure nothing is missed, combined with a team of over 100 expert variant analysts to ensure everything is correct. The result? Users are able to analyze their search terms in a simple, evidence-rich interface to determine relevance.

Mastermind is used by thousands of labs all over the world to quickly uncover and interpret novel variants with useful gene and variant summary information with the confidence you will identify more disease-causing variants by reviewing all relevant articles, and streamline workflows by rapidly triaging variants to focus on known disease-causing genes. It’s simple. Genomenon is a mission-driven company. We are motivated to save and improve the lives of patients with genetic disease by making genomic evidence actionable. In pursuit of this mission, we have a very ambitious goal of curating the entire human genome, and we have made great progress towards that goal this year.

You’re probably asking yourself, what does a fully curated genome look like? I’ll tell you. A fully curated human genome comprises every disease, every gene, every variant, every reference, every database, interpreted to clinical guidelines, all evidence annotated, displayed, and accessible. In this process, we have recognized the value of reviewing this type of evidence in providing insight for disease causation at the gene level, too. The evidence supporting both known and newly characterized gene-disease relationships is growing exponentially month by month, leading to information overload. This is the challenge that we are rising to meet with these gene-disease curations. The curation of genes at the gene level to characterize these gene-disease relationships is vital to ensuring clinical diagnostic assays are properly prioritized and interpreted.

In pursuit of our ambition to curate the human genome, we are excited to announce that we recently completed curation of the clinical exome for over 5,500 genes. That amounted to many decades of curator effort, all of which is being made available in Mastermind 3.0 as we will be describing in the remainder of this webinar.

Some key points that I want you to look out for as my colleagues Denice and Betty run through a demonstration of the functionality and a discussion of the content in Mastermind 3.0: first is the magnitude of content. Over 5,500 genes curated at the gene level, over 9,500 total gene-disease relationships, with over 2,000 of them being novel gene-disease relationships, and our ever-growing list of genes curated at the variant level. This incredible information is displayed on our new gene page, which Denice will review.

Second is to remind you that this work resulted from your feedback and insights that we’ve gained from listening to your needs. Examples of features that were a direct result of feedback from Mastermind users like you include gene-level information, an updated Focus View page and workflow to allow you to view articles easier, protein shifts to explain particular GLP matches, and filtering for a protein position range change.

Finally is the context that this is an initial launch, and while we are very proud of the result here, and it is already met with a very positive response, we are dedicated to continual product improvement. As Denice and Betty give their presentations, please look out for places in the interface where this new and useful information is stored.

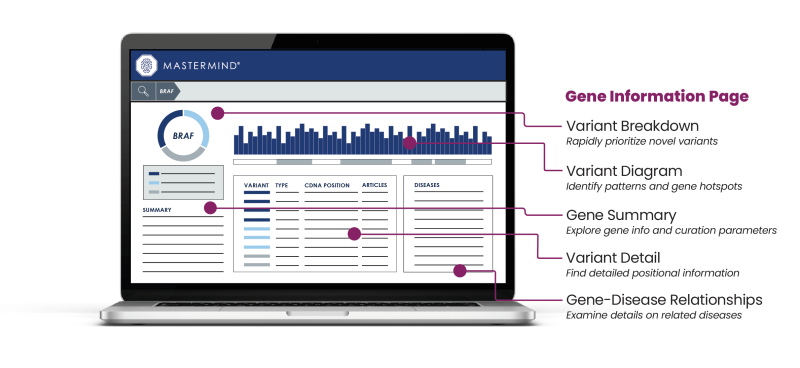

I’m going to go over a few of those pieces, the first of which is on the left-hand side of the screen that Denice will be showing. That is the variant breakdown. That will help you rapidly prioritize novel variants. The variant diagram is similar to the variant diagram that you know and love in Mastermind, with some enhancements. Gene Summary helps you explore gene info and curation parameters. Variant Detail is detailed positional information. Gene-Disease Relationships, located on the right-hand side, allows you to examine details on related diseases. With that, I’d like to pass the controls over to my partner in crime, Denice, who will be running through a live demo of Mastermind 3.0.

DENICE: Alright! Thanks so much, Dan, for the introduction, and setting the stage for this demo. My name is Denice, and I’m a field application scientist. What that means is I spend a lot of time talking to Mastermind users, providing demos and training, and answering your technical questions. In those conversations with users, I hear a lot of feedback, and channel that directly back to Dan. We really value it, we listen. It’s because of feedback from our users that I get to do this, to be able to come back to our users and show them how their ideas for Mastermind have actually become reality. So let’s jump right in. As Candace mentioned at the top, the features I’m going to demo are part of the professional edition of Mastermind, so keep in mind that some basic users may have a different experience.

To get to the new gene information page, all you have to do is type a gene into your search bar. You can combine your gene with a disease phenotype or therapy and still be directed to the gene page. We’ll keep it simple with a search for the gene APOB. Immediately, we’re brought to the new gene page, which has a beautiful, sleek new interface. I’m going to be walking through quite a few new features, as well as some existing features that we’ve made enhancements to.

Starting here on the left side, this circle diagram — this new feature is a graphical breakdown of variants by type. You can see the total number of variants identified in Mastermind for this gene here on this tab, which is about 5,600. In addition to that, we now display the total number of variants that have been submitted to ClinVar. You can compare variants that have been published in the literature to those that are clinically observed, and just toggle between these two tabs up here by clicking on them.

For example, if I click on the ClinVar tab, you’ll notice that the circle diagram has changed because I switched over to actually view the ClinVar data. Now, we’re looking at the ClinVar breakdown of variant by type. The types of variants are listed below the graph here. If you want to see the breakdown by classification, you can just click on any of these variant types to see that information dropdown. So, I’m going to click on “missense.” Now, I can see the breakdown of how many of those in ClinVar are pathogenic, benign, VUS, etc.

At Genomenon, we are on a mission to curate the genome. When curated variants are available for the gene you’ve searched, you can do this exact same thing over here on the Genomenon tab. If you want to see a breakdown of variants that we have classified, you do the same thing. Every time you see this little caret symbol, that means there are more goodies to click. So if you do that, here, you can see the breakdown of variants that have been curated by our team. This breakdown section gives you a holistic view of what kinds of variants have been reported, and what kinds have been published in your gene of interest. Having that kind of info can help you quickly prioritize both novel and known variants that you’re interpreting.

Scrolling down here to the next section, the Gene Summary. This is all new information that we’re bringing into Mastermind. Here, you’ll find a functional summary of your gene. You’ll also see other names that your gene might go by, the canonical transcript, as well as the chromosome location. Then, we’re also showing information for protein domains in this gene. You’ll see the name of that domain and then the codon range as well.

Below that, we are showing information about protein shifts. Thanks to GLP, Mastermind is are aware of these protein shifts. When you launch a variant search, you get a highly sensitive return of the evidence. Knowing this protein shift information then gives you the context for why certain variants can be described in multiple ways in the literature, giving you the clarity to figure out what the different nomenclatures are meaning.

Scrolling down a bit more now to focus on this section for intrinsic metrics, which are useful in the application of ACMG gene-wide criteria. Here, we display information from a number of different sources, all nicely assembled to enable efficient gene curation. Betty will dive into this in greater detail, so stay tuned for much more on that. The gene summary that I talked about so far and the intrinsic metrics are also viewable as a popup. For example, if I scroll up a little bit to this little icon here, we can click on this, and it will open up a window showing us this information in a tidy space that’s very convenient. In this window is also where you’ll find the footnotes, which describe the different thresholds for the different scores. You’ll notice that we have some footnotes here, and this is where you can find those details.

Closing the window now, we can move on to the section for curated gene-disease relationships, which is up here on the right side. Our fantastic curation team, the same team who has been bringing curated variants to Mastermind, has accomplished this incredible milestone of curating the clinical exome at the gene level. This amounts to over 5,500 genes, over 9,000 GDRs, that are all live in the platform now. We are of course still actively working to curate even more as we set out to curate the human genome. What you’ll see in Mastermind in this section is the name of the disease, the strength of the association. If that strength is definitive, then we will also show you the inheritance pattern. Many of these GDRs are unique to Mastermind, and are not found in other gene-disease databases. So, not only are you benefiting from seeing those novel associations otherwise not reported, but seeing the GDRs also helps expedite your curation by prioritizing the variants to analyze.

Moving back up toward the variant diagram here — this is very similar to the variant diagram on the traditional Mastermind interface, with a few notable enhancements. The navigation of this diagram is the same: you scroll in and out to zoom in and out, and you can click and drag to pan across the length of the protein. In the upper right, you can see that this highlighted area essentially corresponds to what you’re looking at in relation to the entire diagram. I’m going to zoom all the way out at this point. Our x-axis is the length of the protein, and the y-axis is the number of variants at that protein position. We can hover over any of these peaks along this diagram, and we can see the total variant count at that position. For here, at position 1,000, there are 11 variants, and we’re also showing you the top 10 most studied variants, and that’s indicated by article count.

This diagram is interactive with the table down below. Right now, if you look at the table, it’s not filtered; this is just all the variants in the gene. But if I click on any of these peaks, the information down below will change, now showing me only variants at that position 1,000, which is the peak that I clicked up in the diagram.

Another new feature in the diagram is this track below the x-axis. We have these gray bars that represent protein domains. These are the same domains listed in the gene summary section that we talked about earlier, just now visually represented along the length of the protein. Hovering over these bars, as you can see that I’m doing, will show you the name of that domain and then the codon range. This bit is also interactive with the table below, so I can click on this domain, and then the table below acts like a filter to show me all the variants in that domain in this table. Domains might be hotspots for interesting variants, so now I can focus on those in the list down here.

Moving down toward that list, the entries here are filtered by this range of codons here because I have clicked that domain up in the diagram. The new feature is that users can enter any amino acid range into the search bar, so I can type in whatever I want. For example, I’ll type in 50 to 55, and you can see that the list of variants in this table is now filtered for that subset. You can also choose the order in which you see these variants in the table. You can sort by any of these headers. You can sort by variant, type of variant, cDNA position, or article count.

The icons down here that we show next to the article number, on the left, when you see the Genomenon logo, indicate that the variant has been curated by our team. The logo on the right, which is the NIH logo, that is indicative of a ClinVar record existing for this variant. Noting when these little logos are present or absent, or shown in combination, that gives you a quick impression of what content will be available when you actually jump to the article views in Mastermind, and immediately tell you whether that variant has been clinically reported.

Finally, to actually view the articles themselves, it’s as easy as clicking on any of these numbers that correspond to the variant you’re interested in. For instance, I expect to see 13 articles when I follow this link here, and since I have both of these icons, I expect a ClinVar record and Genomenon-curated content. Clicking on that page takes you to the Focus View interface, which we’re looking at now.

I can explore those 13 articles, look at related variants, and of course, there’s the ClinVar record, which we were primed to expect, because of that icon on the previous page. Then, of course, our Genomenon-curated content. Remember, when we have curated content, to click on this button over here for “View Interpretation.” This is where you’re going to see all of the supporting evidence behind our provisional call. If we click on this, it’ll take you to the interpretation page for this variant. Our curators believe in showing their work, and it’s all been laid out and organized here to help expedite your interpretation. With that, I am excited to introduce one of the stars of our curation team, Betty Matthias, who will be diving into the data and the work that made the 3.0 Gene Page possible.

BETTY: Hello! Thank you so much, Denice, for that introduction. As previously stated, I am a project manager here at Genomenon, with many of my responsibilities involving variant analysis, internal SOPs and procedures, as well as strategy. The next portion of today’s webinar is going to be discussing Mastermind 3.0, with a few specific topics, and all of this will be from a variant analysis perspective. The topics that I’ll discuss today are the gene summary, the gene-disease relationships, and also the intrinsic metrics. When we discuss each one of these topics, we will answer the questions of what is it, why did we do it, how did we do it, and why is it important.

First, we’ll go over the gene summary. When you search for a gene in Mastermind, as Denice showed, this result will include a RefSeq summary, gene synonyms of how that gene might be described in the literature, as well as transcript and chromosome information for your gene. Lastly, at the bottom, there will be information about domains and protein shifts, which we’ll discuss in more detail later.

This gene summary page was included in Mastermind 3.0 out of needs in the clinical diagnostic community. This actually came from feedback from our own variant analysts and our procedures, as well as user feedback. The main need here is just that this gene-level data is dispersed among many different resources. This causes variant analysts to have to go to each one of these resources and very tediously accumulate all of the information that they might need before they even begin curation of their variant.

We addressed this need by first researching and identifying all of the reliable and accurate gene-level resources. We next gathered data from the different resources, followed by normalizing, analyzing, and curating that data. Lastly, we uploaded that data into Mastermind 3.0. This is very important, because it does reduce the steps and time required during variant pre-curation, and provides a lot of that information at the tip of your fingers. More specifically, seeing these protein shifts helps users understand how Mastermind’s genomic language processing works. This is really in two different places within Mastermind: we see this shift awareness in the match text results on the variant page, as well as in the curated content in Mastermind.

So, we’re actually going to dig into an example of how you can use this protein shift to your advantage as a variant analyst. To begin this example, let’s all pretend that we don’t have Mastermind available for our use, and that we’re performing this search on our own. For this particular example, we’re curating for the gene ALDH7A1 and the variant p.Q453R. When I search for this one variant description, I only get one reference article with no additional information. This leads to a VUS interpretation with only population and computational data supporting that curation.

However, if we use Mastermind, we would probably approach this differently. First, I would search for my gene of interest, which is ALDH7A1, in Mastermind 3.0. I then go to the protein shift section in the gene summary and see this particular result: for this gene, we have an initiator methionine, which has been removed at position one, and we have a transit peptide from positions 1 to 26. Now, as a curator, I know that the first 28 amino acids for my gene are involved in protein shifts. As I have listed here, different combinations of these shifts can alter how the nomenclature might appear. Interestingly enough, the initiator methionine and transit peptides are very common shifts I see as a variant analyst. If not on a daily basis, I see these shifts all the time. These shifts are a very common phenomenon regarding nomenclature.

For this particular example, once I have that knowledge, I can use that. I take my variant of Q453R and subtract 28 amino acids numerically from that position, and I get Q425R as another possible variant description. Then, if I follow the same procedure and search for the two variants, which are really the same variant but have two different descriptions (453 and 425 versions), I get three original articles. After double-checking that this nomenclature is representing the same variant, I get a likely pathogenic classification due to two patients being identified in two articles, as well as functional evidence in the third article. This is significantly different from the previous result.

The great thing about using Mastermind is that our genomics language processing is aware of peptide shifts, and can accommodate the various nomenclatures seen in publications. There are two places that you might find the shift awareness: first, in our curated content, we take these protein shifts into consideration during curation and perform nomenclature correction when necessary. Second, this peptide shift awareness may also be seen in the match text results.

As you can see, I searched our original variant, the 453, and all of these results are shown in Mastermind. If you look at the match text specifically, which I highlighted in the bottom right corner, you will see that both the 453 as well as the 425 have many matches. This peptide shift awareness helps users understand how their variant may be described in the literature and also how our genomics language processing works.

Next, we’ll dig into the gene-disease relationships. This particular section includes the disease name, the strength of the relationship, and the inheritance pattern for any gene that we have curated up to this point. Again, this was born out of a need in the clinical diagnostic community, both for our variant analysts internally as well as our users. First, gene-disease associations are dispersed across many different databases, which results in our interpreters going to many different resources trying to accumulate and compare all of these data points. Next, the data within these resources are sometimes contradictory. Sometimes we see contradiction with the lumping and splitting, disease terminology, conflicting evidence, refuted associations, and many other components of that gene-disease relationship. This results in curators having to spend a lot of time making sure that they identify what exact resources they should be searching for. The last need is just that these resources sometimes lack pertinent entries. In my experience, I’ve had some variant curation projects in which I have to curate variants for a gene that has no association according to those databases, more accurately, it just hadn’t yet been assessed.

We are so pleased because Genomenon has met the needs of the community by curating the clinical exome for more than 5,500 germline genes. Approximately half of the gene-disease relationships are novel associations that have not been described by other resources. In addition to the initial dataset of the 5,500 genes, gene-disease curation is a continual process here at Genomenon, where we are dedicated to growing this database. This data was created in response to user feedback, as well as our own variant curation procedures. Therefore, we invested 75 curator years in a systematic, scalable, and “gene-first” gene-disease curation that is now available in Mastermind 3.0.

There are several advantages to using Genomenon for your gene-disease relationships, the first one being that our procedure is built off of the accepted and standard guidelines as published by ClinGen. As you all are probably aware, this includes clinical and functional evidence and specific components that are found in the literature and other databases, which is exactly the procedure we follow here at Genomenon. Additionally, we have a very large team of expert scientists skilled in GDRs. This includes many curators, project managers, team leads, as well as a whole other team of quality control individuals. We have genomics language processing and internal tools that are super powerful and allow us to be very comprehensive, sensitive, and accurate in the curations that we perform.

When we look at the results of our gene-disease relationships up to date, we really have two different categories of information. The first category is previously identified gene-disease relationships. We know this data exists out there; there are other institutions also putting efforts towards this work. When we look at previously identified gene-disease relationships in our process, we begin by performing a systematic review of the existing curations associated. We want to make sure and have a very good understanding of what the community knows. We want to know about the phenotypic spectrum, inheritance pattern, and disease mechanism, and all of those relevant pieces of information. After that review of the existing curations, we spend a lot of effort to augment that data with additional lines of evidence when available. Additionally, we also have steps to reexamine any of the contradicting evidence and see if there’s any valuable information that might bring more insight to that contradiction.On the other hand, as I stated earlier, we have very many novel gene-disease relationships in our database as well.

As you can see on the right, we have a summary image of the general procedure that we follow. If you’re familiar with ClinGen’s guidelines on how to perform this procedure, it’s identical essentially. The first step of our procedure is our genomics language processing and AI, which has built out an infrastructure that organizes the literature to enable our human experts to perform every other component of this process. So next, we begin pre-curation, which is where curators will first look at the known associations, if there are any. Again, we look for everything that’s already known about that condition and make sure we are aware of those things. Next, we might start beginning to make decisions about lumping and splitting for any conditions that we predict to find during our curation process.

Next, we move on to curation. This is is essentially where the meat of our work is done. Again, this is performed by our curation team, where they spend a lot of time assessing databases, as well as historical and new publications. Lastly, once all of the data has been accumulated, we will apply the ClinGen scoring framework in our general step of scoring the data. This is followed by quality control by a quality team that we have here at Genomenon, composed of many specialists as well as a product quality manager. Once all of that data has been curated by our human experts and quality controlled, again by more experts, we release this data into Mastermind.

This is important because it impacts which variants will be assessed for curation and diagnosis. Gene-disease relationships are often a precursor to variant interpretation. It also reduces the steps and time required during pre-curation and allows curators to get to the answer faster. Next, it also provides associations that are otherwise not reported in any other database. As I stated earlier, about half of our gene-disease relationships in Mastermind were previously described by other resources. Most of the time, our curation highly aligns with the curation that’s been performed by others. However, many times, we have a different call. The examples I’m about to show you are a highlight of situations in which the evidence supports a different classification. The three examples I’ll show are gene-disease relationships that have recently been assessed by Genomenon and will be released into Mastermind soon. So I’ll start by giving you a sneak peek.

For this first example, we assessed the gene AQP1 and pulmonary arterial hypertension. ClinGen evaluated this in 2021 and came to a moderate classification. Genomenon then evaluated this data in 2023 and found an additional paper that was published in 2022 with two new families. This evidence supported a definitive classification, which is really exciting. This example just highlights the impact of frequent analysis on gene-disease relationships due to the ever-increasing amount of published literature.

SH2B1 and obesity is the next example. This was not identified or evaluated in any other gene-disease databases. When Genomenon approached this gene, we found much evidence, specifically, three papers with clinical cases, as well as another paper that functionally links this gene to the signaling pathways relevant for obesity. We were able to reach a definitive classification using the evidence provided. This example highlights one of the many reasons that Genomenon is dedicated to curating these gene-disease relationships. There’s so much significant data available, and that’s out there, but it just requires curation in order to be actionable.

The third example is for the gene ATG7 and an autosomal recessive form of ataxia. ClinGen identified and curated this association in 2022, and came to a strong classification. Genomenon evaluated the same gene-disease relationship, and there was no additional evidence, newly published or otherwise, that we identified. ClinGen currently has all relevant information identified in their curation. However, due to there being only one publication with clinical connection between this gene and disease, the evidence supports only a limited classification until further publications bring more insight.

The last thing we’ll talk about today is the Intrinsic Metrics. This particular section of Mastermind 3.0 includes an indication of whether there is a ClinGen Variant Curation Expert Panel (or VCEP) published for your gene of interest. We also provide a table format for PVS1, PP2, and BP1 that includes the metric source, the metric value, and also the Genomenon evaluation.

This data in Mastermind 3.0 was founded from the need, first published in 2015 in the classic Richard et al. paper, where they describe these three intrinsic criteria: PVS1, PP2, and BP1. Very quickly, PVS1 is often applied to null variants where loss of function is the disease mechanism. This includes nonsense, frameshift, and splice sites, in addition to others. There’s PP2, which is applied to missense variants in a gene where benign missense variants are uncommon, and pathogenic missense is a common mechanism of disease. Lastly, there’s BP1, which is applied to missense variants when primarily truncating variants are known to cause disease for that particular gene-disease relationship.

This data was born out of a need, the first need being that the application of PVS1, PP2, and BP1 are very loosely defined in those original guidelines. Additionally, the data metrics are dispersed across many different databases, which requires us, as analysts, to go to those different databases, identify those metrics, record them, and compare them. Next, the strengths, limitations, and thresholds are dispersed among many different sources. Lastly, some of the metrics that have been suggested to be used for these intrinsic decisions have no threshold recommendations.

How we did this is, we first researched industry guidelines, database publications, and any other published standards. Once we had performed all of that research, we then accumulated a robust set of resources and thresholds. After that, we gathered all of those metrics and normalized, analyzed, and curated that data. Lastly, we uploaded the data into Mastermind 3.0. This is important, because again, it reduces the steps and the time required to make these intrinsic decisions, and also provides transparency for the data that we use for our own variant curation procedures.

I wanted to dig down a little bit more into how I might use this information as a variant analyst. I recently worked on a curation project of the gene LDLR, where we worked on over 25,000 variant paper associations, and ended up curating over 50,000 patients. As you all are aware, as variant analysts, the intrinsic decisions are very important and can impact how you approach curation of a particular project. The first thing I would do as a variant analyst when I have my gene of interest would be to search in Mastermind 3.0 and see that there is a ClinGen Variant Curation Expert Panel for this gene. When this happens, as I can see indicated by the “yes” here, I would go to ClinGen, look at the VCEP, and apply all of their suggestions regarding the intrinsic guidelines.

However, let’s pretend we don’t have that data available, and I’ll show you how I would continue on. So from here, we have to take the idiosyncrasies of our gene-disease relationship into mind. I know that LDLR is associated with familial hypercholesterolemia, which is a generally mild condition that does not impact reproductive fitness. I also know that the inheritance pattern is autosomal dominant. In this particular scenario, I would remove the gnomAD data due to the likely negligible impact on reproductive fitness, making this data slightly less reliable for this scenario. I can then easily look at all of the other data in this graph and can see that this suggests that PVS1 is applicable. In this situation, that does match the ClinGen VCEP.

Our mission at Genomenon is to save and improve lives by making genomic information available. We realize that empowering our users with this genomic information is an imperative component of that mission, as we all work together to save and improve those lives. This is why we’re providing this new genomic intelligence in our Mastermind 3.0.

CANDACE: Wow, thank you, Betty! That was awesome. It looks like we have enough time for some questions, so I’m going to invite Denice, Dan, and Betty back to answer them. Denice, I will turn it over to you.

DENICE: Alright, thanks so much, Candace. So let’s see, got the first question here for Dan: What is the source of our protein domain info that we’re displaying in that Gene Summary section?

DAN: UniProt is our source for the protein domain information that we display.

DENICE: Perfect, quick, and easy. Another hopefully quick and easy one, what’s the version of gnomAD that we’re using?

DAN: As of right now, we’re using gnomAD version 2. Since the recent update of gnomAD version 4, our team is currently assessing the potential use of that version in the future.

DENICE: Alright, thanks so much. Next one here is for Betty. Can you tell us a bit more about how you use GLP for gene-disease curation?

BETTY: Sure, that’s a really good question. I’ll start off by comparing it to Mastermind. You all are familiar with the features and capabilities that are built into Mastermind, such as the search tools for genes, variants, phenotypes, therapies, and all of those capabilities. Another capability that you might be aware of as well is all of the filtering. For example, there’s an in vivo functional filter, and there’s a much longer list of filters available, but essentially, all of those tools and capabilities are built into a different infrastructure which we use for our curation process.

Essentially, we have these capabilities built into a different organization that allows our curators to know all of the things that we need to know from the literature. We’re able to easily prioritize things, stay organized, and systematically work our way through the literature. This is also very helpful for our quality control as well, where we have certain capabilities enabling them to systematically review all of that data as well.

DENICE: Awesome, thanks so much. Alright, let’s see here… For Dan, is it possible to see details on the strength of the association for those gene-disease relationships? For example, what publications were used to score?

DAN: Great question. As of right now, no, but as we continue to develop Mastermind, that information will definitely be available for users to see. In addition to that, we currently display the SOP used for gene-disease relationships in the FAQ, so that goes into more details.

DENICE: One thing I’ll add to that is that we also, for the variant curation, the SOP is also available — If you’re on the interpretation page, there’s a little link right below where the little banner for the interpretation is. It’s a link to a PDF, and that’s our SOP for variant curation, and like Dan said, we’re also going to make that available in the FAQs for the gene curation work.

Alright, for Betty now: Have you curated somatic variants? Because we only showed examples for hereditary variants today.

Betty: Yeah, that’s a great question. I will say that a lot of Genomenon’s efforts for variant curation have started with hereditary or germline conditions. However, we have begun the process of looking into what somatic variant curation might look like here at Genomenon. We’re starting to dig into that from the variant curation perspective, and we hope to make it available, potentially, someday in the future in our Mastermind interface as well.

DENICE: Awesome. Sort of related to that, Betty, another question for you: is the team continuing to curate more genes beyond what we have already done with the clinical exome?

BETTY: Excellent question. The clinical exome is a pretty loose term, depending on who you ask, and we definitely have goals to go beyond that. On one hand, we could say we’ve already reached the clinical exome, and since we’re still continuing curation, we’re definitely on the path to curate as much available information as there is out there regarding publications and what we can find. We definitely have not hit the limit of information out there that we can curate.

DENICE: Yeah, definitely. Just tying that back to the previous question, our mission is to curate the genome, so yes, that does absolutely mean that we’re going to do somatic curation, and we’re going to continue with more genes outside the clinical exome. Perfect, thanks so much. For Dan: how can I see what transcript a variant is on from within the variants table? Just to give a little bit more context to this question, when you’re looking at the variant diagram, and you can see all the variants at that position, Mastermind is not making any decisions for you on what transcript you’re interested in. When you look at position 50, you might see some changes, for example, arginine at 50, but on some other transcript, there might be a different amino acid at position 50, so you might also see tryptophan 50, or something like that. So, how can users tell, in the variants table, when they’re looking at a discrete missense variant or something, what transcript is that one on?

DAN: Great question. We have a column in the variant table called “cDNA position” where it lists cDNA positions, and if you hit that dropdown caret, all of the transcript information will be displayed there.

DENICE: Perfect, thanks. Just a reminder, generally in the interface, whenever you see a caret, that means there’s something to see behind or below. If you’re looking for a feature, it might be behind a caret. If you ever have questions when you’re in the interface, and you’re looking for something that you feel like is there but just can’t find it, there’s a “contact us” button right within the application. It’s in the top right menu bar, and says “contact us”. That will open up a little chat box for you to send your message to us. That message goes to me, but also to our whole support organization so that we can get you the answer to your question. Definitely don’t be shy to reach out to us using “contact us” because you can use that for questions, but you can also just drop in your feedback and your ideas. It’s a great place to get in touch with myself, Dan, and our whole team.

DAN: And be curious! Click the carets, check it out.

DENICE: Alright. For Betty: for genes where a GDR has not been previously identified, how do you select the genes to study, and where do you start in selecting diseases to vet?

BETTY: That’s another very good question. We began our prioritization by essentially deciding what dataset we first wanted to release into Mastermind 3.0, and that was the clinical exome. Being aware of what’s considered the clinical exome dictated all of the associations that we were going to look for. Interestingly, approximately half of that clinical exome didn’t have gene-disease relationships yet curated, so that’s where many of what is currently novel in Genomenon’s database has been prioritized.

Regarding the second part of that question, about how we even begin the process of trying to find what phenotype or disease we’re looking for, this ties directly back to our genomics language processing and our internal software. It’s incredibly aware of phenotypes and oncology terms and all of the relevant pieces of information that might pique our interest. When we approach a particular gene or disease — well, I guess it’s from the gene perspective — we’re going to scour through the literature and look at all those oncology and phenotype terms. In general, we start from the clinical perspective, but if we notice a thread, we’re going to follow that thread and see if we can weave a bigger story with the evidence that’s available.

DENICE: Awesome, yeah. Betty, maybe you have some more flavor to add to this comment that I’m about to give, but we’re taking a gene-first approach when it comes to those GDRs. One approach is to take a disease-first approach, which is to pick a disease and try to find all the genes. We’re flipping the script on that and going gene-first, using all of our robust internal tools, like Mastermind, to then look at a gene and see what gene-disease relationships are there.

BETTY: That’s a very important clarification. We are doing it from a gene-first perspective, meaning that we are looking at a gene and finding any and all associations that might be in the databases or published literature. This means that when this association is published into Mastermind and you search for your gene of interest, you can be confident that the list of associations is comprehensive according to recent curation.

DENICE: Perfect. This question is probably for Dan: is the new gene page available for just pro users or also for basic users?

DAN: Great question. It’s available for all users, but certain information on the gene page is only available for pro users. We have a limited number of genes that will include the classification breakdowns and gene-disease relationships for, but if you want access to all of the classification breakdowns and all of the gene-disease relationships, that part’s only available in pro.

DENICE: Alright. Also for Dan: is there an interface with EndNote or other literature platforms?

DAN: For curated variants, there is an ‘Export to Report’ button that exports all of the PMIDs and the criteria that they support. You can download all the articles returned by Mastermind, instead of those used in curation, via a CSV download button in the articles list.

DENICE: Perfect, so just to clarify, the ‘Export Report’ button is on the interpretation page. When you search for a variant that has a curation, click on ‘View Interpretation’, and the export report button is in the bottom left corner. The ‘Export as CSV’ option exists on the regular interface, with an export button right above the articles list, just to give some further clarification on where those buttons live. That’s where it is.

Another question here, probably for Dan too: Is it possible to download all of the so far curated gene information in Mastermind?

DAN: As of right now, no, it’s not possible to download all of the curated gene information in Mastermind. However, we will be updating the gene-disease relationships as well as other gene information quite often, so just keep an eye out, and you might see the gene that you’re looking for.

DENICE: Perfect, thanks so much, Dan.

CANDACE: Alright! Thank you all so much, Dan, Denice, and Betty, and to all of you who are attending today. Here’s one last look at the bit.ly link to create your free Mastermind account. A reminder to look out for your email with the recording of the webinar to review and share. Of course, feel free to reach out to us with your questions at support@genomenon.com, or if you’d like to schedule a custom demonstration for your team, we’d be happy to do that. We hope to see you all again in our next event, and have a wonderful rest of your day.